Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919) was born as the youngest of the seven children of Alvah and Vesta Walker. She was raised from an early age in the spirit of progressive non-conformism that characterized the household. While they were believing Christians, the parents taught their children to always question the regulations of various faiths. The children were also raised to question the prevailing dress codes of the time, traditions that many feminists and free thinkers of the day felt inflicted moral, mental and physical suffering on women with heavy, constricting clothes that restricted circulation and collected dust and dirt. Mary worked on the family farm as a child, eschewing women’s clothing in favor of more practical labor garments.

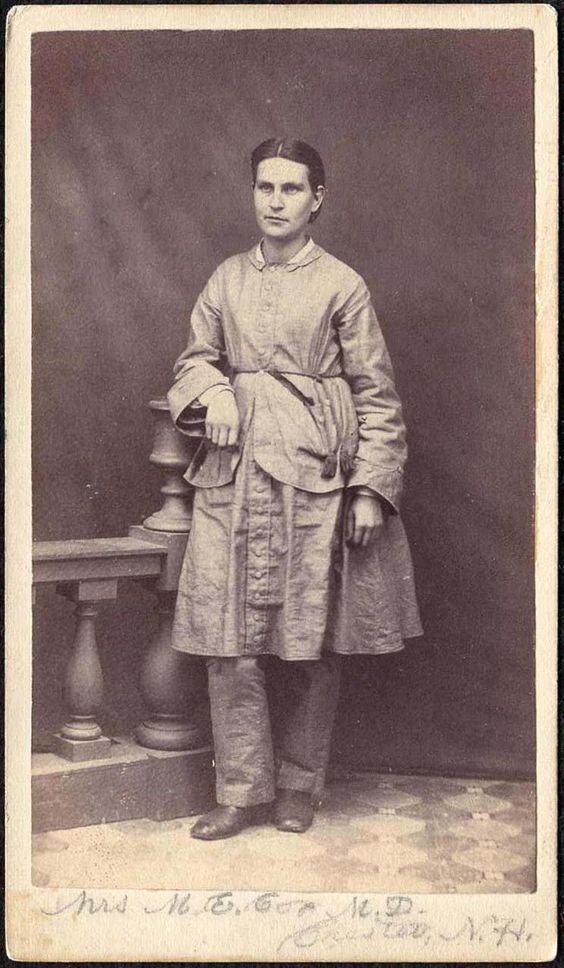

Mary and her siblings attended a primary school started up by their parents, then moved on to Falley Seminary in Fulton, New York, a place of education that emphasized modern social reform alongside academic studies. She found an interest in medicine through her father’s medical textbooks and graduated with honors from Syracuse Medical College as a doctor, the only woman in her class. She married a fellow medical student the same year. True to her feminist views, she wore a short skirt over a pair of pants for the wedding, retained her family name and refused to “obey” her husband in her vows. The two opened a joint practice but the public’s lack of trust in a female doctor caused their business to flounder and she later divorced her husband because of his infidelity.

When the American Civil War broke out, Walker volunteered to the Union as a surgeon but was rejected because of her sex. Refusing to perform the simpler tasks of a nurse, she eventually found employment as an unpaid civilian volunteer at a temporary hospital operated at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C. From there, she moved on to work as an unpaid field surgeon near the front lines, serving at the battles of Fredericksburg and Chickamauga, becoming the first female surgeon of the U.S. Army. Staying true to her views on clothing, he wore men’s garments at work, claiming they enabled her to perform her job more effectively.

In September 1863, she was finally employed by the U.S. Army as a contract acting assistant surgeon (civilian), giving her a salary and a legal status with the military. She frequently crossed Confederate lines to treat wounded civilians. In April 1864, one such trip ended with her capture by Southern soldiers just after she finished helping a Confederate doctor perform an amputation. She was charged with espionage and kept in the infamous Castle Thunder prison in Richmond, a place known for the brutality of the guards and the diseases running rampant among the inmates. Walker was forbidden to help treat her fellow prisoners and she herself suffered partial muscular atrophy during her time there. After four months, she and several other doctors were exchanged for Confederate medical personnel captured by the Union. For the rest of the war, she served as the supervisor of a women’s prison in Kentucky and as the head of an orphanage in Tennessee.

Following the Civil War, Walker became an author and prominent supporter of health care, women’s suffrage, temperance and dress reform, often arrested for wearing men’s clothing. She argued for many years that the Constitution, as well as the legislation of several states, had already given women the right to vote and Congress only needed to enact enabling legislation. She later changed her stance and supported a new constitutional amendment granting voting rights to women but this caused her to lose popularity within the feminist movement.

In November 1865, Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor. The award was new at the time and requirements were still fairly loose. During the Civil War, numerous individuals received it for capturing Confederate battle flags, being both items of symbolic value and important means of battlefield communication, but also for re-enlisting in the Army, serving as Lincoln’s Honor Guard and, in more than 500 cases, due to administrative incompetence. In Walker’s case, the reason was that after the war she was lobbying for a brevet promotion to commissioned officer status. This was legally impossible, since she wasn’t an actual commissioned officer to begin with. The medal was intended as an alternate reward, as is made clear in the official citation:

Mary Edwards Walker “[…] faithfully served as contract surgeon in the service of the United States, and has devoted herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the field and hospitals, to the detriment of her own health, and has also endured hardships as a prisoner of war four months in a Southern prison while acting as contract surgeon; and Whereas by reason of her not being a commissioned officer in the military service, a brevet or honorary rank cannot, under existing laws, be conferred upon her; and Whereas in the opinion of the President an honorable recognition of her services and sufferings should be made.”

In an effort to bring some order to the awarding of the Medal of Honor, the Medal of Honor Board deleted 911 names from the roll in 1917, including Walker’s. Nevertheless, she continued to proudly wear the medal for the last two years of her life and her medal was posthumously restored by President Jimmy Carter in 1977.

You can learn more about the incredible individuals who served in the Civil War and shaped America as we know it today on our three American Civil War Tours: A Nation Tested, March to the Sea and War in the West.